October 10, 2019

Blog

On Keeping Goals

By Matthew Putman

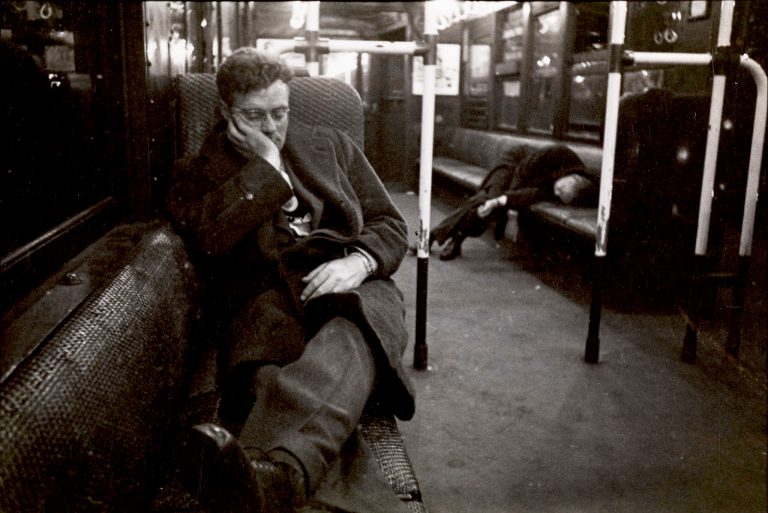

35mm photo by Stanley Kubrick. Men sleeping in a subway car, 1946. Courtesy of the Museum of the City of New York.

Christopher Hitchens was able to write and submit an eloquent, publishable, witty 2000 words after an evening of drinking Johnny Walker Black Label…while still on his first coffee—but I am no Christopher Hitchens.

Today, as I write this, I’m reconsidering the entire concept of having a goal. I realize I unconsciously fight against goal-oriented behavior while passionately pushing toward it. This fraught perspective is the kind of tension I need.

I’m beginning to see that achievements often stem from a combination of cloudily defined long-term goals (that become clearer as we approach them), and obsessive, crystal-clear micro goals. Like the flash of a photograph, micro goals occupy short durations: a single meeting, a project. Never a lifetime.

Mammals evolved to survive in the moment. Of all mammals, the multilayered human cerebral cortex gifts us with the ability to perceive our own mortality. Aren’t we lucky?

This perception drives us to race against time. Poets express it best. Edna St. Vincent Millay: “My candle burns at both ends;/It will not last the night;/But ah, my foes, and oh, my friends—It gives a lovely light!” Or Dylan Thomas: “Do not go gentle into that good night/Old age should burn and rave at/Close of day/ Rage, rage against the dying of/The light.”

It seems to work something like this: young goal-setters have freedom to explore. They build, search, ponder, struggle through fights, love affairs. They bite into life, driven to work their way out of it. They cultivate support and mentorship, but also build an internal sense of confidence that does not ask for validation. The final output burns inside them, an obsession for getting something right—but they allow accidents, mistakes, and mishaps to inform their process. An internal quality control, so to speak.

Process is important to them—but there is never any question of not arriving at the final goal. As Julie said about taking on a challenge at a very young age, “Of course I had never done it before, but I didn’t think there was any way I couldn’t do it.” Which is not the same as having doubt and pushing forward—it is almost an ignorance of human weakness. This is a beautiful blind spot to have.

Only later do many of these builders and doers realize that their vision is not universal. And that if they had followed the rules and let the boundaries and barriers of systems inform their internal vision of themselves, they may never have developed their unabashed confidence in life…and never reached “impossible” heights. Antoinette Roberson expressed this beautifully in last week’s podcast.

In my interviews with my father and Julie Orlando, I learned, completely by accident, something mundane but telling. They both built wooden boxes using power tools when they were much too young to use power tools. They made their boxes for their collections. The boxes themselves were shelters for exploration, a place to consolidate the objects they felt were valuable at the time.

As I traveled through Europe this spring and summer, I saw Leonardo DaVinci anniversary exhibitions. He was an amazing idea collector. At any given moment, the ideas in his notebooks may have only had a secret relevance for him. Edison was another collector/inventor. Edison labs had a room filled with everything—from railroad spikes to elephant tusks—for no other reason than at one point, Edison or his team of inventors wanted these materials available for undefined projects. Photography consumed Stanley Kubrick. At 17 years of age, he took spontaneous images of street life in black and white for Look Magazine. These first photos are obsessive, rigorous, expressive, free. A short video of the great AI and microscope innovator and educator Marvin Minsky—in his 80s, shot in his house—looks like Mary Condo’s hell of hoarding. Certainly, these pieces of his past may have influenced him as he continued to invent until he passed away.

These assortments, collections, memories, notebooks, and photos are kept compulsively. The writer, dreamer, inventor, or collector gathers these fragments in the moment without knowing, or even particularly caring, about what this preservation will become or how exactly it will aid their future creations. They are touched and must keep. Joan Didion writes of the tendency in her wondrous essay “On Keeping a Notebook.” This kind of collecting is not an impulse for reality. It is the impulse of invention.

Mechanics obsessed my friend and colleague, Julie—the insides of machines, how they worked. She needed to viscerally experience—she needed to spill the guts of her Nintendo in order to understand it. Later she needed to do the same with tools, machinery, hardware, and the inside of factories

In all cases that I have observed, there is also this tense juxtaposition of obsession and boredom. This is certainly true for me. Maybe boredom is not the right word, but a strong desire to move on to learn and build the next thing. It is an intense compulsion that leads to new micro goals.

My father often calls me out of the blue with an idea for an invention that has almost nothing to do with the invention he had yesterday. It’s rarely a fleeting thought either. He generally goes as far as patent searches and drawings, and sometimes to building. One year before the World Cup, we spent several weeks inventing a new type of indoor soccer ball that felt like a regular soccer ball when you kicked it. We went to every store to try different materials. We sewed the materials together ourselves. And we wrote a patent for it. A micro goal, certainly. Embedded in a time period where we were also building our first super-resolution microscopes for Nanotronics.

This is not unusual for the human mind. Both of my kids have notebooks filled with drawings, puzzles, and equations. Rooms with dioramas, miniatures that they built (especially my daughter), and entire worlds architected from diverse materials. Do kids generally start this way, until they are told to focus on “one thing?”

How does inspiring and achieving macro goals differ? The micro is fleeting and in focus—a snapshot of life. My guess is that the outlines of ideas of what the world should look like to them is more static than they think, often because of its vagueness. The macro goal becomes the constant in an otherwise dynamic life.

This can be something like me saying that the world should have replicators and no scarcity. Or that the joys of our planet can be universally available, regardless of money. Or that humans can work together on micro goals with a passion that prevents us from building destructive militaries and war. The macro exists always in our imagination. It haunts us when we read, go to the theatre, listen to music, visit museums. It the atmosphere that supports life. The home from which everything grows. The box that a litany of boxes and collections will flow from.

One builds for the future by focusing on building that house. Maybe, if we are lucky, we will all build boxes, and fill them with the objects and tools that make up our individual lifeblood and oxygen, or maybe we will not.

The confidence and conviction that we will reach our final goals, and the micro discoveries along the way are well worth the trip.

***